DUBAI: From awesome animation to devastating documentary, here are our top films of 2025 to date.

‘A Complete Unknown’

Starring: Timothée Chalamet, Edward Norton, Elle Fanning, Monica Barbaro

Director: James Mangold

Chalamet gained deserved plaudits for his portrayal of arguably the greatest singer-songwriter in the history of modern Western music, Bob Dylan, in Mangold’s biopic — and he does a fine job, capturing the star’s fragile ego and magnetic charisma. But the true star of “A Complete Unknown” may be Barbaro as Dylan’s fellow folk-music star Joan Baez, she embodies Baez’s fiery nature, intelligence and talent brilliantly. Mangold navigates the many myths (often self-generated) surrounding Dylan to create an utterly convincing look at his early career, up to the infamous furor created when he turned his back on folk purism by using electric instruments. Biopics of musicians have a checkered past, but “A Complete Unknown” is definitely one of the good ones.

‘Ocean with David Attenborough’

Directors: Toby Nowlan, Keith Scholey, Colin Butfield

Starring: David Attenborough

Perhaps the year’s most vital movie so far is a documentary fronted by a 99-year-old. In “Ocean,” the venerable English biologist and broadcaster presents a gorgeously shot, awe-inspiring and immersive film that examines the damage done in the depths of Earth’s oceans by the thousands of super-sized fishing trawlers operating around our planet constantly. With his trademark authority and passion, Attenborough lays out just what is at risk if they continue their destruction. But crucially, he also offers hope: the oceans, scientists have discovered, can recover at remarkable rates. “As nature documentaries go, it’s hard to imagine “Ocean” being bettered,” our reviewer wrote.

‘Flow’

Director: Gints Zilbalodis

Writers/producers: Gints Zilbalodis, Matiss Kaza

Quite how a film with no dialogue manages to be so engaging, thought-provoking and moving is a mystery. But this Latvian animation about a black cat struggling to survive alongside a small group of other animals in a post-apocalyptic world in which water levels are rising dramatically is all of that and much more. It’s a slow-burner, meditative at points, but with moments of great peril and small heroics. From the beautifully rendered landscapes to the astonishing attention to small details in the animals’ movements, noises and behavior, “Flow” is clearly a labor of love, and deservedly picked up Best Animated Feature at both the Oscars and the Golden Globes.

‘The Phoenician Scheme’

Starring: Benicio del Toro, Mia Threapleton, Michael Cera, Riz Ahmed

Director: Wes Anderson

This 1950s-set story of an arms dealer whose near-death experience leads him to try and fix his relationship with his estranged daughter, a nun, is not the best Wes Anderson movie, but it’s still a Wes Anderson movie, and so delivers typically stunning cinematography, great (and heavily stylized) performances from a stellar ensemble cast (including those mentioned above plus Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Richard Ayoade, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Willem Dafoe, Bill Murray, and many more), plenty of dark humor, and a singular world view. If only every director’s “not their best” work could match up.

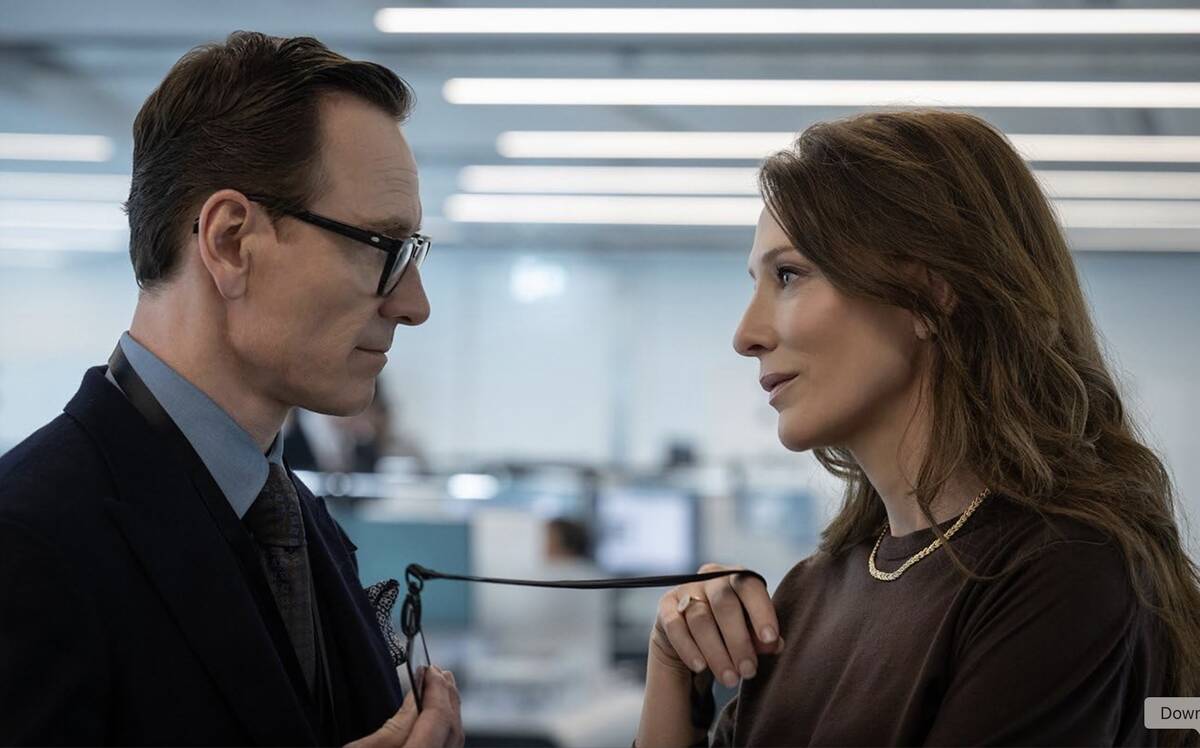

‘Black Bag’

Starring: Cate Blanchett, Michael Fassbender, Marisa Abela

Director: Steven Soderbergh

The conceit at the heart of “Black Bag” — a husband-wife spy duo — is nothing new; nor is its ‘twist’ of one being assigned to investigate the other when they are suspected of being a traitor. But with Soderbergh at the helm, and actors as accomplished as Blanchett and Fassbender as the leads, this super-stylish thriller sets itself apart. Fassbender plays British intelligence officer George Woodhouse, whose wife Kathryn (Blanchett) is just one of five people suspected of leaking some top-secret software, but she quickly climbs to the top of that list when George discovers her secret Swiss bank account.

‘Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl’

Voice cast: Ben Whitehead, Peter Kay, Lauren Patel, Reece Shearsmith

Directors: Nick Park, Merlin Crossingham

There is so much to admire about Aardman Animations’ sixth installment in this action-comedy series about a provincial English inventor and his long-suffering dog. Not least that it proves to certain film studios (hey Marvel) that it’s still possible to tell an entertaining yarn in 90 minutes or less. With Aardman’s usual jaw-dropping stop-motion skills providing the arresting visuals, and Park and co-writer Mark Burton’s knack for creating storylines that produce giggles and feels for all ages as strong as ever, this was a very welcome return for our two unlikely heroes and their arch enemy Feathers McGraw, out to frame Wallace in revenge for his imprisonment back in 1993’s “The Wrong Trousers.”

‘Sinners’

Starring: Michael B. Jordan, Hailee Steinfeld, Miles Canton

Director: Ryan Coogler

One of the most entertaining vampire films we’ve seen for a while. Jordan is excellent in dual roles as Elijah and Elias Smoke — twin brothers returning to their hometown and trying to outrun their criminal past. Set in the Mississippi Delta in 1932, it’s partially inspired by the legend of the blues musician Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil. The blues plays a major role in the movie too (with some not-so-subtle digs at the fact that some of the blues’ biggest fans would also likely be adversaries of the Black musicians making it), as the twins’ cousin Sammie is a hugely talented musician. The brothers set up their own juke joint, at which Sammie’s the resident star. Then the joint becomes a target for undead forces of evil. “Sinners” is brash, bold, and a lot of fun.