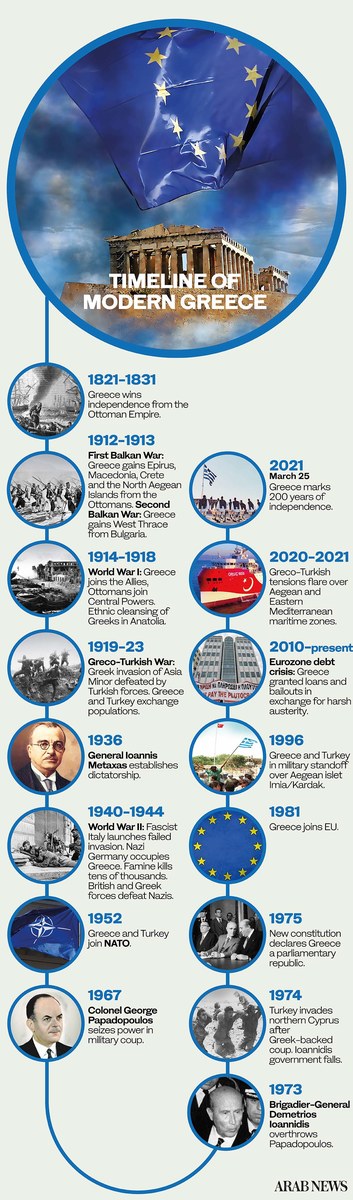

WASHINGTON: This year is one of great symbolism for Greece. The country is celebrating the 200th anniversary marking the beginning of a nine-year campaign that led to the establishment of the modern Greek state in 1830.

Hundreds of events are planned mainly under the auspices of the Greece 2021 Committee set up for the occasion.

It aims to shed light on different aspects of the nation’s re-birth and the successful campaign to determine its affairs independent of the Ottoman Empire. What was the Greek War of Independence, and how have Greek-Turkish relations been affected by its emergence?

To start with, it is important to stress that the nine-year process that led to the Greek state’s modern formation was not a war of independence as conventionally understood. It is more accurate to depict it as a rebellion, indeed a revolution, since the rebels were far from constituting an organized army.

Moreover, no Greek state existed at the time, capable of fighting a conventional armed conflict against the organized Ottoman army and navy. Lastly, the revolution had multiple starting points because Greeks were dispersed in a large geographic area inside and outside of the Ottoman Empire.

To illustrate this point, the start of the Greek Revolution occurred in February 1821, when Alexandros Ypsilantis published a manifesto for a call to arms in today’s Romania. He argued that the time had come for Greeks, wherever they were, to fight “for Faith and Homeland.”

Ypsilantis was the head of the Friendly Society (Filiki Eteria), an organization set up by members of the Greek diaspora in Odessa in 1814, that became a focal point to aid the revolution through financial, logistical and political support.

The rebellion Ypsilantis envisioned was suppressed pretty quickly, as the revolutionaries were inadequately prepared and thus easily defeated after the czar’s intervention and support of the central government of the Ottomans.

Yet the torch was carried on by rebels further south, in Peloponnesus, as the revolution was eventually crowned with success in 1830 when the full independence of the Greek state was recognized by the then great powers of the UK, France and Russia. In contrast with 1821, Europe’s powers realized that Greek autonomy and its eventual independence served their interests better than open suppression.

Greek War of Independence 1821 - 1829, Turkish general Ibrahim Pasha in front of his tent, wood engraving after drawing by Jeanron, circa 1827. (Alamy)

Further, a great wave of sympathy among Western public opinion towards the revolutionaries became widespread by 1825-1826. It had religious connotations as Christians were fighting Muslims (at least in some theaters of conflict), yet was mostly the result of the successful attempt to link ancient Greece’s image in the eyes of the west with the modern-day struggle of its successors on the ground.

The link was flimsy in ways more than one, but that counted for little. Philhellenism became a powerful force that ultimately allowed the revolutionaries to reach their cherished objective. By 1832, the Ottoman Empire also accepted the inevitable that Greece was now a member of the community of nations.

Its struggle became a rallying cry for other populations in 19th-century Europe. Poles, Hungarians and many others rightly saw in the Greek Revolution the passionate expression of the ideals of the French and American Revolutions and proceeded with the formation of their own states over time.

The Greek Revolution of 1821 is therefore a momentous event in world history, far bigger in consequences than the small state that was formed. For the revolutionaries and the political class of the emerging state, however, their priorities were more immediate: How to make sure Greece would get bigger and bring under its jurisdiction the majority of Greeks still subject to Ottoman rule.

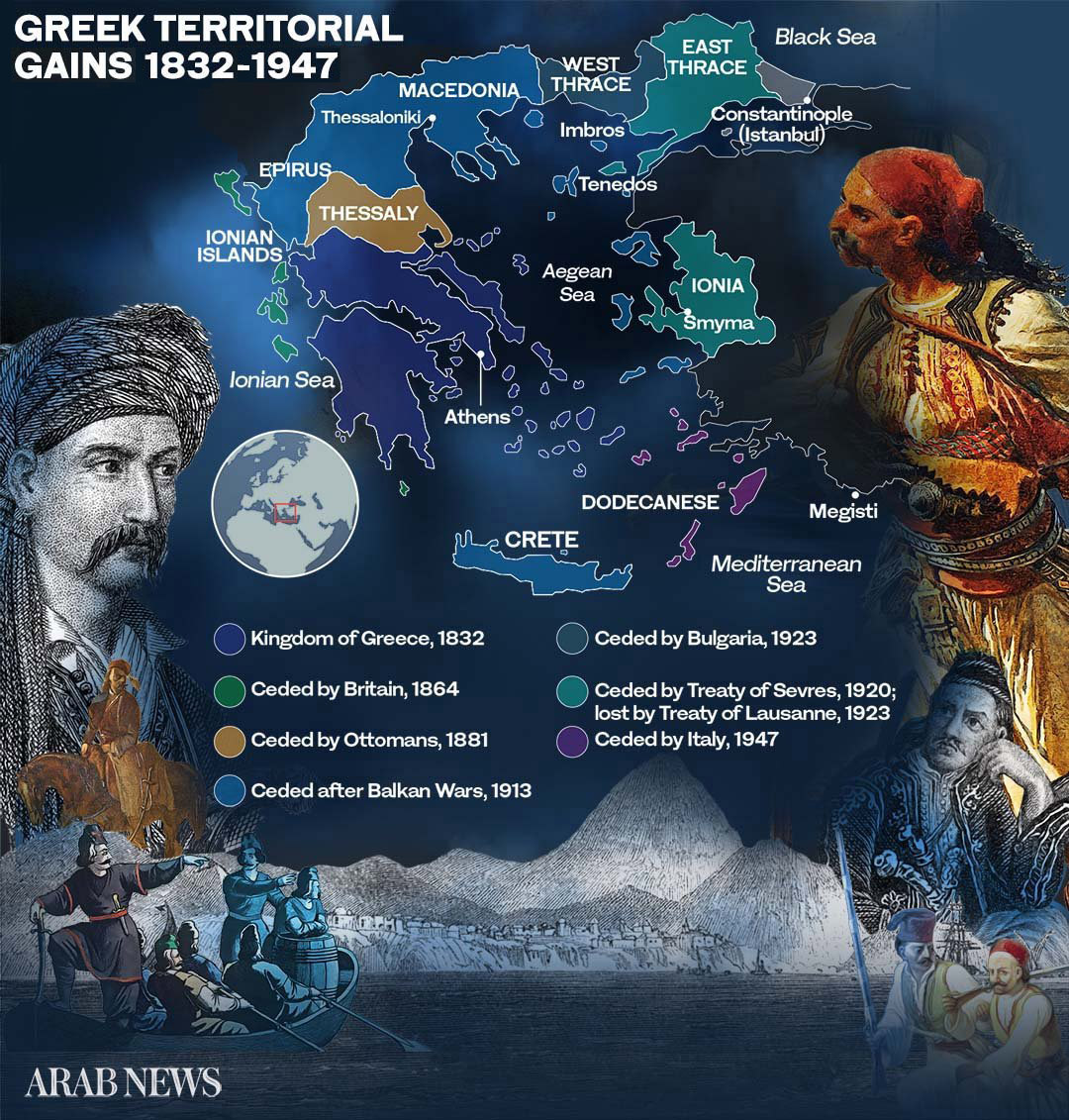

To do so, they needed to fight the Ottomans, not once but many times over until the boundaries of the country were firmly set in 1947 and after the Dodecanese Islands became part of the state. Two decades earlier, the Lausanne Treaty of 1923 ended the war between Greece and Turkey, setting the boundaries of the latter country.

Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his comrades-in-arms had earlier rejected the failed Ottoman Empire. Importantly, the nationalist fervor that led to military victory and a new set of diplomatic accords with Greece and other European powers had been originally inspired by the same nationalist zeal that had engulfed their Greek counterparts a century earlier.

Modern observers of Greek-Turkish relations often have difficulty in understanding the intensity of their present-day disputes, unaware of the centrality of the “other” in the historical process that led the two states to come into being.

As I have argued elsewhere, it is precisely their historical state formation, including identity formation and the setup of national consciousness in opposition to the other side (rather than on its own terms) that accounts for the emotional outbursts and limited rationality in sustainable conflict resolution mechanisms characterizing a large part of their conflict-ridden relationship.

How so?

Museum employees unwrap an artwork depicting Greek revolution heroine, Laskarina Bouboulina in the new museum dedicated to the Philhellene foreign volunteers who fought and died for Greece on March 12, 2021. (AFP/File Photo)

From the 1820s and for an entire century, one side’s victory in the battlefield (or, more often, the diplomatic decision-making circles of the great powers, on which the Greek state was clever enough to rely) was the other side’s loss. Starting from 1830 and until the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, generations of Greeks were determined, if not always battle-ready, to liberate “enslaved Hellenism” from Turkish rule, or Tourkokratia.

In the process, they also managed to incorporate other parts of today’s Greece from countries such as the UK (such as the Ionian Islands in 1863). The next step followed in 1881, when again the great powers convinced the Ottomans to cede Thessaly and a part of Epirus to Greece. By the early 20th century the Ottoman Empire’s decline had accelerated and Greece used that to its advantage.

The Balkans Wars of 1912-13 pitted Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria against the Ottomans, as well as each other, over Macedonia and parts of Epirus. The union of Crete with Greece was also completed at that time.

Greece had managed to enlarge its territory by more than 60 percent and its desire to liberate the “enslaved brethren” appeared close to success by 1921. The crumbling Ottoman Empire, combined with the diligent policies pursued by Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, allowed Greece to reach its peak by 1921.

Yet 10 years of continuous war had taken its toll and the irredentism manifested in the Greek army’s march deep into central Anatolia came to a crashing halt once Ataturk launched a devastating counterattack. Lausanne put an end to hostilities but not before Greece and Turkey embarked on a population exchange, with religion the main criterion for the exchange.

Greek Prime Minister Constantin Caramanlis (L) and Turkish Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel (R) talk during the first Greek-Turkish summit since the Cyprus war ended at Palais d'Egmont in Brussels, Belgium, on May 31, 1975, to find a solution between the two countries mainly on the Cyprus problem. (AFP/File Photo)

Vestiges of Hellenism remained in the new Turkish Republic, as the patriarchate was allowed to remain in Istanbul, and a sizable Greek minority with it, too. In the years that followed and once the war was over, Greek-Turkish relations have been met with ebbs and flows.

Tensions have been high more often than not, especially over Cyprus, which remains divided to this day and overshadows attempts for a normalization of relations. However, it is also important to stress, given the centuries of coexistence between the two peoples, that their relations have also gone through periods of accord and mutual respect.

Immediately after the war, Ataturk and Venizelos established cordial relations, not least due to their genuine desire for lasting peace and Ataturk’s revolutionary reforms. In 1934, Venizelos even proposed that the Nobel Peace Prize be given to Ataturk.

Friendly relations turned sour after the passing of the two leaders and did not return until the late 1990s with another period of rapprochement. The long shadow of history, with 1821 at its heart, continues to affect Greek-Turkish relations in multiple ways.

---------------------

* Dimitris Tsarouhas is a professor of international relations, specializing in Greek politics, Greece-Turkey relations, EU-Turkey relations and EU affairs. Twitter: @dimitsar