RIYADH: Global food insecurity is far worse than previously thought. That is the conclusion of the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 report published this week by a coalition of UN entities, which found that efforts to tackle undernourishment had suffered serious setbacks.

As countries across the world fall significantly short of achieving the second UN Sustainable Development Goal of “zero hunger” by 2030, the report notes that climate change is increasingly recognized as a pivotal factor exacerbating hunger and food insecurity.

As a major food importer, the Middle East and North Africa region is considered especially vulnerable to climate-induced crop failures in source nations and the resulting imposition of protectionist tariffs and fluctuations in commodity prices.

“Climate change is a driver of food insecurity for the Middle East, where both the global shock and the local shock matter,” David Laborde, director of the Agrifood Economics and Policy Division at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, told Arab News.

“Now, especially for the Middle East, I think that the global angle is important because the Middle East is importing a lot of food. Even if you don’t have a (climate) shock at home, if you don’t have a drought or flood at home — if it’s happened in Pakistan, if it’s happened in India, if it’s happened in Canada — the Middle East will feel it.”

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report has been compiled annually since 1999 by FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the UN Children’s Fund, the World Food Programme, and the World Health Organization to monitor global progress toward ending hunger.

During a recent event at the UN headquarters in New York, the report’s authors emphasized the urgent need for creative and fair solutions to address the financial shortfall for helping those nations experiencing severe hunger and malnutrition made worse by climate change.

In addition to climate change, the report found that factors like conflict and economic downturns are becoming increasingly frequent and severe, impacting the affordability of a healthy diet, unhealthy food environments, and inequality.

In this photo taken on July 2, 2022, Iraqi farmer Bapir Kalkani inspects his wheat farm in the Rania district near the Dukan reservoir, northwest of Iraq's northeastern city of Sulaimaniyah, which has been experiencing bouts of drought due to a mix of factors including lower rainfall and diversion of inflowing rivers from Iran. (AFP)

Indeed, food insecurity and malnutrition are intensifying due to persistent food price inflation, which has undermined economic progress globally.

“There is also an indirect effect that we should not neglect — how climate shock interacts with conflict,” said Laborde.

In North Africa, for example, negative climate shocks can lead to more conflict, “either because people start to compete for natural resources, access to water, or just because you may also have some people in your area that have nothing else to do,” he said.

“There are no jobs, they cannot work on their farm, and so they can join insurgencies or other elements.”

DID YOUKNOW?

Up to 757 million people endured hunger in 2023 — the equivalent of one in 11 worldwide and one in five in Africa.

Global prevalence of food insecurity has remained unchanged for three consecutive years, despite progress in Latin America.

There has been some improvement in the global prevalence of stunting and wasting among children under five.

In late 2021, G20 countries pledged to take $100 billion worth of unused Special Drawing Rights, held in the central banks of high-income countries and allocate them to middle- and low-income countries.

Since then, however, this pledged amount has fallen $13 billion short, with those countries with the worst economic conditions receiving less than 1 percent of this support.

Protesters set out empty plates to protest hunger aimed at G20 finance ministers gathered in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on July 25, 2024. (AP/Pool)

Saudi Arabia is one of the countries that has exceeded its 20 percent pledge, alongside Australia, Canada, China, France, and Japan, while others have failed to reach 10 percent or have ceased engagement altogether.

“Saudi Arabia is a very large state in the Middle East, so what they do is important, but also they have a financial capacity that many other countries don’t,” said Laborde.

“It can be through their SDRs. It can also be through their sovereign fund because where you invest matters and how you invest matters to make the world more sustainable. So, I will say yes, prioritizing investment in low- and middle-income countries on food and security and nutrition-related programs can be important.

Saudi Arabia does produce wheat but on a limited scale. (SPA/File photo)

Although the prevalence of undernourishment in Saudi Arabia has fallen in recent years, the report shows that the rate of stunting in children has actually increased by 1.4 percent in the past 10 years.

There has also been an increase in the rates of overweight children, obesity, and anemia in women as the population continues to grow. In this sense, it is not so much a lack of food but a dearth of healthy eating habits.

“Saudi Arabia is a good example where I would say traditional hunger and the lack of food … become less and less a problem, but other forms of malnutrition become actually what is important,” said Laborde.

In 2023, some 2.33 billion people worldwide faced moderate or severe food insecurity, and one in 11 people faced hunger, made worse by various factors such as economic decline and climate change.

The affordability of healthy diets is also a critical issue, particularly in low-income countries where more than 71 percent of the population cannot afford adequate nutrition.

In countries like Saudi Arabia where overeating is a rising issue, Laborde suggests that proper investment in nutrition and health education as well as policy adaptation may be the way to go.

While the Kingdom continues to extend support to countries in crisis, including Palestine, Sudan, and Yemen, through its humanitarian arm KSrelief, these states continue to grapple with dire conditions. Gaza in particular has suffered as a result of the war with Israel.

A shipment of food aid from Saudi Arabia is loaded on board a cargo vessel at the Jeddah Islamic Port to be delivered to Port Said in Egypt for Palestinians in Gaza. (KSrelief photo)

“Even before the beginning of the conflict, especially at the end of last year, the situation in Palestine was complicated, both in terms of agricultural system (and) density of population. There was already a problem of malnutrition,” said Laborde.

“Now, something that is true everywhere, in Sudan, in Yemen, in Palestine, when you start to add conflict and military operations, the population suffers a lot because you can actually destroy production. You destroy access to water. But people also cannot go to the grocery shop when the truck or the ship bringing food is disrupted.”

While Palestine and Sudan are the extreme cases, there are still approximately 733 million people worldwide facing hunger, marking a continuation of the high levels observed over the past three years.

“On the ground, we work with the World Food Programme (and) with other organizations, aimed at bringing food to the people in need in Palestine,” Laborde said of FAO’s work. “Before the conflict and after, we will also be working on rebuilding things that need to be rebuilt. But without peace, there are limited things we can do.”

FAO helps food-insecure nations by bringing better seeds, animals, technologies, and irrigation solutions to develop production systems, while also working to protect livestock from pests and disease by providing veterinary services and creating incentives for countries to adopt better policies.

The report’s projections for 2030 suggest that around 582 million people will continue to suffer from chronic undernourishment, half of them in Africa. This mirrors levels observed in 2015 when the SDGs were adopted, indicating a plateau in progress.

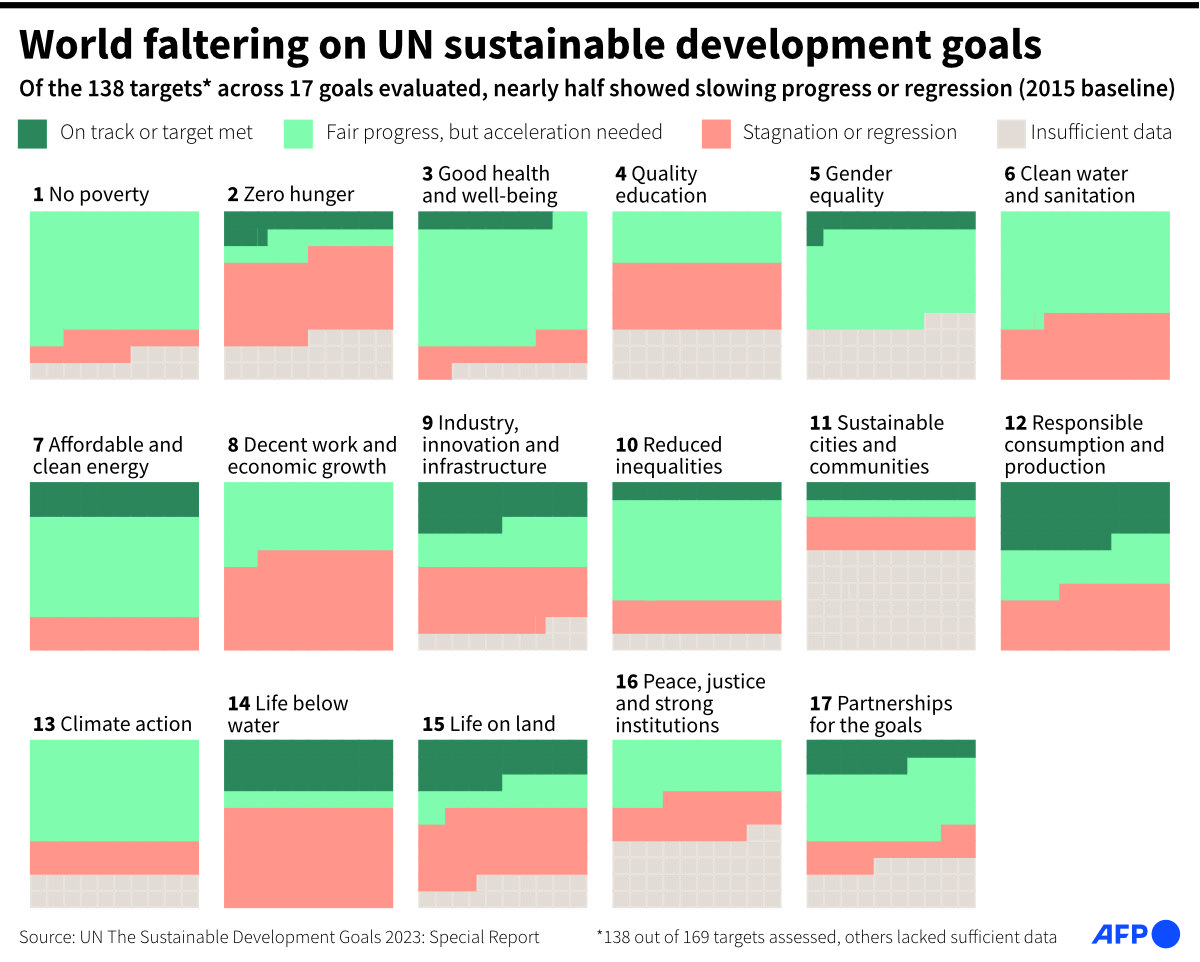

Graphic showing progress on the United Nation's 17 sustainable development goals since the baseline of 2015. (AFP)

The report emphasizes the need to create better systems of financial distribution as per this year’s theme: “Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition.”

“In 2022, there were a lot of headlines about global hunger, but today, this has more or less disappeared when the numbers and the people that are hungry have not disappeared,” said Laborde, referring to the detrimental impact of the war in Ukraine on world food prices.

“We have to say that we are not delivering on the promises that policymakers have made. The world today produces enough food, so it’s much more about how we distribute it, how we give access. It’s a man-made problem, and so it should be a man-made solution.”